The film centers on two women – an older one and her young daughter-in-law – and their needs are absolutely primal. They begin every day with the task of surviving, and they have developed a grisly commerce. They ambush and murder wandering samurai, and steal their weapons and armour to exchange for food. Indeed, the films’ opening images illustrate their handiwork, as two ronin are killed, stripped, and dropped into a deep pit.

The two woman soon encounter the vagabond soldier Hachi, a friend of the old woman’s son Ushi. He has returned from fighting in the wars that are raging throughout the countryside, and he tells tales of how he narrowly escaped death and how Ushi wasn’t so lucky. Hachi is loud and exaggerated, and gives the impression of being one not to be trusted. The women certainly don’t, as they treat him with distain. They want to know about the death of Ushi, and if Hachi could have prevented it. The old woman later tells the daughter-in-law exactly what’s on her mind.

“He may have killed Ushi himself.”

It’s a second encounter with Hachi, however, that first lets us in on where the story is headed. The younger woman is sitting by a lake, pounding some laundry with a stick, when Hachi appears. He talks to the girl, and it’s obvious from watching his eyes that he desires her, as she sits barelegged and spread-eagled on the dock. The older one sizes him up immediately, and warns her. “He wants you.” Thus begins the bizarre triangle – the lecherous Hachi pursues the younger woman, and the older one desperately tries to keep him away.

Ah, but it’s not quite that simple. The younger woman succumbs to her needs and begins to visit Hachi in his hut at night. The older one follows her and watches as they have sex. She runs away from the scene and then stops and grasps her breasts then wraps herself around an old dead tree. The camera pans up the tree, and the sexual symbolism is unmistakable. Her primal urge to maintain her way of life is being challenged by another – her desire for sex.

The following day she goes to visit Hachi and finds him sleeping in the grass. The contradictions in the old woman are brought right to the surface in this brilliant sequence. She derides him as a useless bum as he sleeps, then wakes him and tries to induce him into sex. Shindo shoots Hachi lying on the grass, with only her bare leg visible, and then shoots her from below stepping over and straddling him. This subtle suggestion of sexual tension is masterfully done.

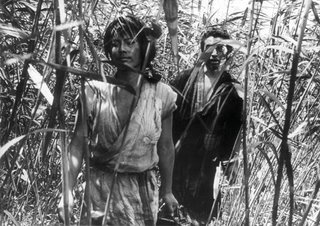

The tale takes a bizarre twist with the introduction of another character – A mysterious samurai who wears a hideous demon mask. The samurai asks the old woman to show him how to get to the main road. As the two wind their way through the long grass, the stranger tells why he wears the mask – to protect his face in battle, because he is extraordinarily handsome.

The old woman leads him directly into the pit, and he falls to his death. She climbs down into the hole to retrieve his valuables, and predictably succumbs to curiosity about this handsome face. She pulls the mask off with some difficulty, and in doing so seals her fate.

The following evening the young woman sets out through the grass for her rendezvous with Hachi, and in a hugely frightening scene, comes face to face with the demon. It’s not hard to figure out what’s going on here – The old woman is using the mask to frighten the younger one away from Hachi, but this takes a tragic twist on a rainy night. The young woman again sees the demon, and runs back home. She slowly gets a fire going in her hut, and the emerging light illuminates a huddled figure on the floor, back turned. The figure slowly turns and is revealed as the demon again. The masked figure starts to plead – “It’s me!!!!” “I can’t get it off!!”

It is revealed to the young woman that the old one has been scaring her, and that the mask had gotten attached to her face – Just as it did the samurai. The old woman pleads to have it taken off and in a chilling scene, the young woman tries to break the mask with a hammer as the old woman screams and cries.

The conclusion of “Onibaba” does not leave you with a neat resolution. Hachi meets his end at the hands of the last person in the world he expected to see, but for the women, it’s a bit unclear. Let’s just say the pit figures into things again.

What a frightening and imaginative thriller this film is! It was done on a budget of next to nothing, but creates images that are impossible to shake. There are no special effects, and no cheap scares. “Onibaba” creates its atmosphere through lighting, location, music, and character…and that brilliant demon mask.