An insufferable film snob wanders off the beaten track, then comes back and talks about what he has seen.

Thursday, June 29, 2006

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Monsieur Klein

The thing is, although the film revolves around the Holocaust, it never really talks about it. Hitler is never mentioned, and German soldiers are seen only very briefly. In the film’s opening sequence, a naked and obviously frightened woman is undergoing a humiliating physical exam. The doctor spends a lot of time examining her face, and finally comes to the conclusion that the woman shares some common features with the “Semite” race. This is masterful, as it quietly establishes that the Jews are starting to be rounded up – with the co-operation of the French.

Mr. Klein (Alain Delon) is first introduced to us off-camera as a gentleman comes to his door to sell a painting. Again, Losey feeds us information in an indirect way, as we listen to the conversation. It’s pretty easy to gather that the man is Jewish, and needs raise some money quickly. Klein knows this, and coldly lowballs the man on price. On his way out, the man says derisively that Klein is taking advantage of people, and Klein retorts that “Sometimes, I don’t even want to buy.”

A pivotal moment ends this small exchange, as Klein sees a small Jewish newspaper on his doorstep, and tells the man that he’s dropped it. The man reaches into his jacket and pulls out his own copy.

Klein makes a trip to the offices of the magazine to try to stop delivery to his address, and this is again a beautifully done example of how we are given information by characters who-tap dance around what they really want to say. Watch Delon’s face when he is told that the magazine’s subscription list is in the hands of the Prefecture of Police. This is the first small crack we see in Klein’s cool façade. There’s also a terrific little exchange as the magazine manager tells Klein that someone may have given him a gift subscription.

“No one would play such a joke on me”

“Do you think we are the subject of jokes?”

The trip to the magazine tells him, however, that there is another man with the same name, and a visit to the man’s address turns up an abandoned apartment and a blurry photograph of the other Klein on a motorcycle.

One day, a love letter arrives that is intended for the other Klein, and it leads Delon to a rich family on the country who are confidantes of the other Klein. As Klein is led into the house, we see that some of their paintings have been taken down off the wall. This isn’t pursued, but it raises the possibility that Klein may have profited from some of their artwork, as well. It also suggests that the other Klein is Jewish. The woman of the house (Jeanne Moreau) comes to Klein at night to retrieve her letter – She is having an affair with the other Klein, and in fact goes out in the middle of the night to meet a man on a motorcycle.

The French police ask for birth certificates of Klein’s grandparents, and he sends his lawyer Pierre for them. At this point in the proceedings, he might be well advised to get out of town, but he is obsessed with finding the other man, and gives the impression that he doesn’t really believe that anything bad is going to happen to him.

The adjective Kafka-esque is often used to describe this film, and it’s an apt description. The French police are investigating Klein, and the other Klein is using him as a decoy. The man on the motorcycle is likely the other Klein, and there’s another instance where Delon is in the same bar with his man, and misses him. He never does actually see the guy. A search for a woman in the photo is maddening; as he is told her name is Isabelle, then Cathy, and then finally, Francoise.

Finally, he comes to the conclusion that he has to get away, and there is a delicious irony in a scene where his lawyer asks about the value of his stuff.

“About 10 million”

“How about 7 or 8?”

When the opening credits roll on this film, they are over a painting – A painting of a vulture pierced by an arrow. This same painting is sold at an auction later in the film, with Klein in attendance. We wonder if he senses the parallels to his own life. He has made money off desperate Jews, and in so doing, given them the means to escape. When his time comes, after he has been rounded up and loaded on a train bound for Germany, we again hear his narration from the opening meeting with the old Jewish gentleman selling his painting. Then the doors slide shut, and the vulture is carried away.

Friday, June 09, 2006

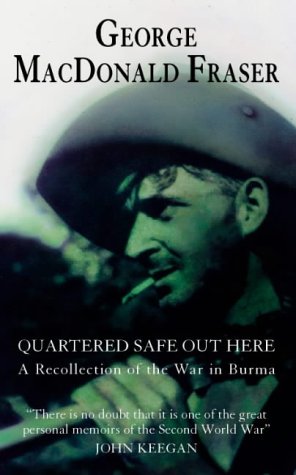

Between the Covers

Fraser’s account of the British campaign in Burma is a vividly remembered time capsule, and also a sobering reminder of the mind-set men shift into when they are asked to kill other men. Just nineteen years old when the book’s events occur, Fraser details the daily lives of his beloved Nine Section (The "Black Cats"), both in the swirl of fierce and bloody battle, and the quiet down moments.

Modern readers may be put off by Fraser’s seemingly casual racism towards the Japanese. He admits to it, and is refreshingly honest about its roots. His thoughts on the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are telling – He is stridently unapologetic, yet can also write, "If it was not barbaric, then the word has no meaning."

The opening lines:

"The first time I smelt Jap was in a deep dry-river bed in the Dry Belt, somewhere near Meiktila. I can no more describe the smell than I could describe a colour, but it was heavy and pungent and compounded of stale cooked rice and sweat and human waste and ….Jap. Quite unlike the clean acrid wood-smoke of an Indian village or the rather exotic and faintly decayed odour of the bashas in which the Burmese lived – and certainly nothing like the cooking smells of the Baluch hillmen and Gurkhas of our brigade, or our own British aromas. It was outside my experience of Oriental stenches – so how could I know it was a Jap? Because we were deep inside enemy-held territory, and who else would have dug the three bunkers facing me in the high bank, as I stood, felling extremely lonely, with a gallon tin of fruit balanced precariously on one shoulder and my rifle at the trail in my other hand."

Monday, June 05, 2006

Pierrot Le Fou

Pauline Kael

Sitting down to dissect a Godard film is like trying to pick fly shit out of pepper with boxing gloves on.

Me

Seriously, when you start becoming a cinephile, you will run into Jean-Luc Godard pretty early on. He was one of the vanguards of the French New Wave, and his influence is immeasurable. He is, however, a tough nut to crack. He takes all your preconceived notions of what a movie should be, and tosses them out the window. I’ve seen most of the stuff from his great early period, and I’m mixed – There are films I like a lot – "Band of Outsiders", "Week-End", "My Life to Live", and " Les Carabiniers" - and ones I’m lukewarm to, like "Alphaville", and "Masculin-Feminin". The one that I keep going back to, however, is "Pierrot Le Fou", from 1966. Of all his stuff, I think this one is the most fun, and was made with the lightest touch.

The film opens with Jean-Paul Belmondo’s unemployed TV exec Ferdinand getting ready to go out to a party with his wife. On the way out, he meets a baby-sitter (Anna Karina) hired by his wife, and there is a small, yet noticeable recognition as they shake hands. More on that later. The party is Godard at his best. These people bore Ferdinand, and as he moves around the room, Godard has the characters talking in TV commercial blurps instead of conversational dialogue.

"The new Alfa-Romeo with its 4-wheel disc brakes"

"I use Odorono after my bath for all-day protection"

Ferdinand leaves, and goes home to find Marianne the sitter sleeping in a chair. He offers to drive her home, and here it’s revealed that the two have been in a relationship. The talk in the car, first with the camera on her as he speaks, then on him as she does, and they basically just run away together.

"It’s in this extended road trip that "PLF" really takes wing. The two wake up at her place, and as they talk, the camera pans past a dead body on a bed, and several machine guns laying about the place. These things aren’t remarked upon, but as they leave the narration goes into a fragmented call-and-respond mode between Ferdinand and Marianne. "This is a story" "All mixed up",etc. From these bits, we start to get an insight into Marianne. She has a brother Paul who is a gunrunner, and she is in some kind of trouble.

As the couple travels into southern France, the film starts to give the sense of being a story being invented, rather than a narrative of events. At one point Belmondo turns and talks directly to the camera. Karina asks him whom he is talking to, and he replies "The audience". Then there is the matter of his name. Marianne always calls him Pierrot, and he, without fail, responds "My name is Ferdinand." In several cases, the characters use the logic of movies, at one point Marianne even says "I saw this in Laurel and Hardy". There are references to "Johnny Guitar" and "Pepe Le Moko", and Sam Fuller even appears as himself at one point.

Godard could usually be counted on to include some kind of political diatribe in his films, which would often have the effect of grinding them to a halt. Think of the garbage men in "Week-End" or the blond firing squad victim in "Les Carabiniers". Here we get the Viet Nam war played as a short moneymaking skit by Ferdinand and Marianne for the benefit of some American servicemen. In this case, it works OK.

Marianne’s troubles eventually catch up to her. Ferdinand is surprised by a couple of hoods looking for her, and they resort to the most unusual mode of torture this side of Monty Python. Ferdinand is put in the bathtub, and they spray water in his face. It seems that Marianne has killed one of their colleagues (The guy on the bed!), and stolen money from them. He tells them where to find her.

The concept of watching something that is just an artifice is brought home as we meet Paul, and realize that he’s not her brother at all, and that poor Ferdinand is just a rube. He gets his revenge in a finale that is arguably Godard’s best. Certainly, the most memorable image in "PLF" is of the deranged Ferdinand, face painted blue, waving dynamite in the air. He has decided to go out, literally, with a bang, and even lights the fuse. It’s somehow fitting that he changes his mind too late, as it burns down to nothing.

The concept of watching something that is just an artifice is brought home as we meet Paul, and realize that he’s not her brother at all, and that poor Ferdinand is just a rube. He gets his revenge in a finale that is arguably Godard’s best. Certainly, the most memorable image in "PLF" is of the deranged Ferdinand, face painted blue, waving dynamite in the air. He has decided to go out, literally, with a bang, and even lights the fuse. It’s somehow fitting that he changes his mind too late, as it burns down to nothing.